Can we change our mindset “in a millisecond as the scales fall from our eyes”? And if it happened would it be contagious?

What if the changes required to drive systemic transformation can happen “in a millisecond, as the scales fall from our eyes”?

Donella Meadows suggested this possibility when articulating her ideas about leverage points – places to intervene in a system.

She also believed that “growth is the stupidest purpose invented by any culture, we’ve got to have limits” and “the goal of the system drives its behaviour”.

An invitation to discuss and be impacted by provocations from two great women in our January Monthly Monday …

When you have had a long career making radio programmes you sometimes hear something on the radio which makes you stop, listen more deeply, and think “I wish I’d made that…”. That happened to me recently with a BBC “Great Lives” sequence, which featured one of my heroes talking about another and gave me the chance to hear a voice I had read on the page but assumed I would never hear, as she died in 2001.

“Renegade economist” (her description) Kate Raworth, inventor of Doughnut Economics, chose Donella (Dana) Meadows, systems thinking pioneer, as her Great Life. In 30 minutes we learn almost as much about Kate as we do about her subject, who she describes as the person she’d most like to meet.

“She was a woman before her time. At the cutting edge of economics today, guess what, it’s complexity economics. It’s really recognizing we need to think in systems, these ideas are resurgent. She said growth is the stupidest purpose invented by any culture, we’ve got to have limits.”

In the world of Leading Through Storms Dana Meadows is probably best known as the co-author of the Club of Rome’s Limits to Growth in 1977. That book was “so confronting that it got roundly trashed by mainstream economics, but its predictions have come true” says Raworth. I remember reading Limits to Growth at university, but like E F Schumacher’s Small is Beautiful it seemed to be quickly allocated to the “don’t get in the way of growth” category of economic cul-de-sacs.

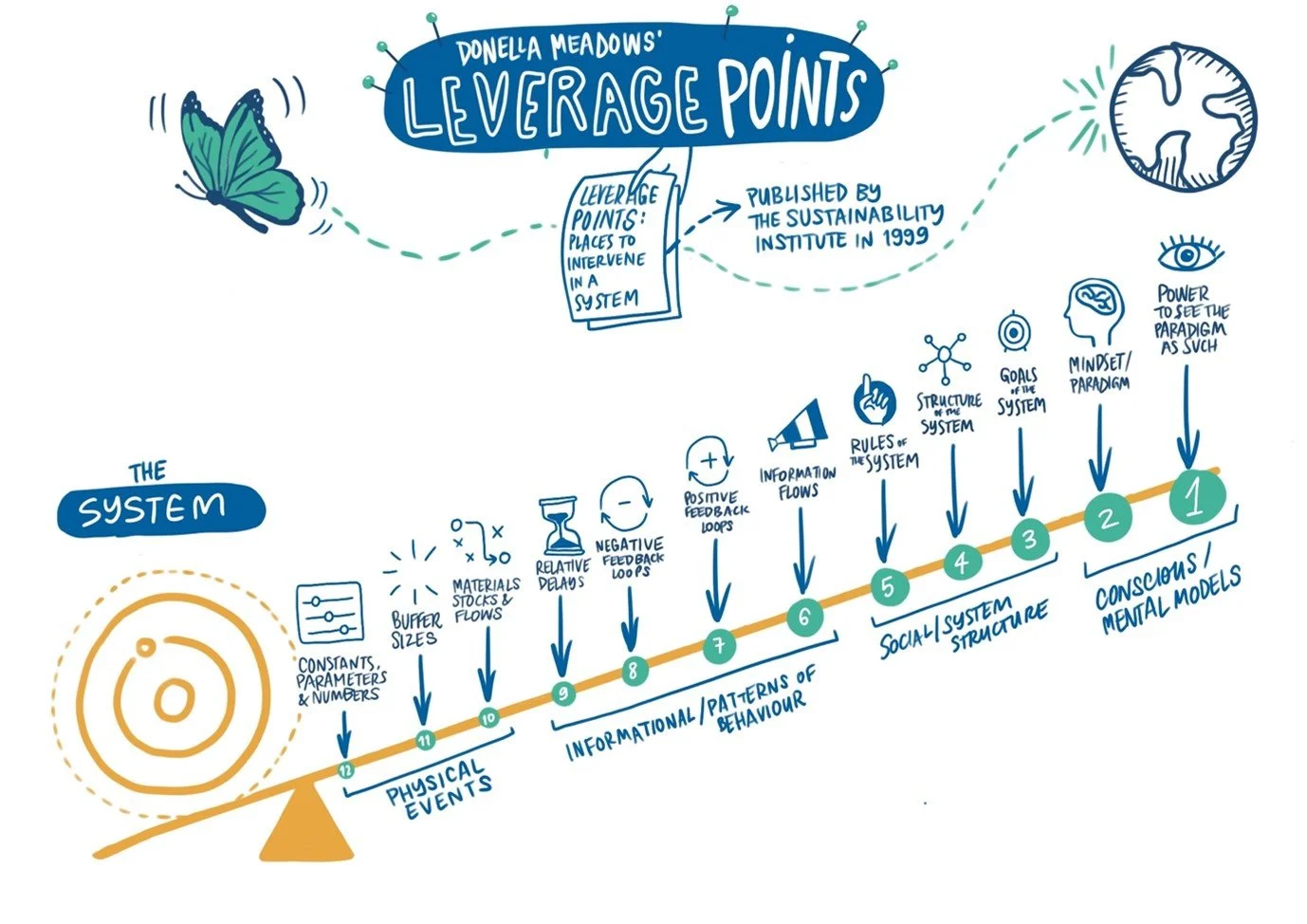

The concept that outlives Dana (published in Thinking in Systems in 2008) is that of Leverage Points. Her great insight in systems thinking was that not every intervention in a system has equal power to change the system. Imagining a long lever on a pivot with the system on one end and the range of things you could do along the length of the lever, she ranked mindsets or paradigms as having the greatest potential to bring change. With thanks to Carlotta Cataldi Illustration who redrew Meadows’ diagram for UNDP, you can see the range of possibilities here:

As Kate Raworth describes in the radio programme, Dana Meadows said that the key thing was mindset or paradigm change and this could “happen in a millisecond as the scales fall from our eyes”. If you’ve been reading and reflecting on the Leading Through Storms approach, you’ll recognize the LTS emphasis on the paradigm and the power to see the paradigm as such which sit at the top end of the lever.

Looking at the Leverage Points diagram, I wonder how mindful are we of how we intervene in systems? Isn’t it tempting, more comfortable perhaps, to do something easier but lower down the lever, rather than the complex uncomfortable mindset stuff further up?

It’s possible to start with the best intentions, wanting to change mindsets (including our own) but sliding back down the lever when difficulties intervene. Many years ago I heard about a project to photograph the least powerful people in supply chains – farmers, factory workers, truck drivers – with the aim of reframing them as “heroes”, triggering a hoped-for shift in audience mindset by having the subjects aim their gaze straight down the camera lens, often with expressions of strength, anger or pain. The idea was to use these images in brand advertising but linking these real people in real workplaces with the dreams of material satisfaction the brands wanted to create was too much for the commissioning team. The photos had to be sanitized before use, and a number of them never saw the light of day.

That was going backwards in Leverage Point terms, but there’s also the intriguing possibility of a multiplier effect in collective mindset change. Tom Oliver, in his book “The Self Delusion” refers to Malcolm Gladwell’s “Tipping Point” explanation of how trends and behaviours spread rapidly through populations, reaching a critical mass in a small subset before the tipping point is reached and then spreading like wildfire to the whole population. Could it be that one day the same thing might occur with our self-identity, our mindsets?

“As the mindset of each person changes, it makes influencing the transition in others more likely. Could we use such social contagion to enable the rapid evolution of a networked sense of social identity [mindset] among the global human population?”

It’s a fascinating prospect – an exponentially increasing number of people with “scales falling from the eyes” all pressing down on the most powerful part of the Leverage Points. Tom Oliver goes on to say:

“It can be unnerving to think about the root cause of social and environmental problems as lying within our individual minds. We like to think about proximate solutions - solve climate change by taxing carbon, solve food shortages by GMOs, solve mental health problems by building green infrastructure in our cities… we cannot ignore the part played by our individual belief systems that, cumulatively across populations, underpin our global institutions”.

For me, he’s describing Dana Meadows’ Leverage Points there, and highlighting that we don’t think enough about the place of our own thinking in the leverage of change.

I’ll conclude with another highlight from the Great Lives programme. As if my pleasure at hearing one of my heroes talking about another wasn’t enough, I then had the delight of hearing Dana Meadows speak, just a few minutes into the programme.

“We can in this culture complain, we can talk about everything we think will never work, but we can’t share our dreams, our hopes, our visions without being labelled naïve, idealist and unrealistic”.

Those words were spoken in the 1970s, but have we progressed all that much from those days? How much more acceptable is criticism and cynicism than dreams, hopes, and vision? Dana Meadows said that “the goal of the system drives its behaviour” but without dreams, hopes and vision how can we guide it?

I’d like to invite you to listen to this programme and join the discussion on the first Monthly Monday of 2024 on January 15th at 16.00 UK.

There are many paths we might follow. Kate Raworth reveals a number of aspects of her relationship with Dana Meadows’ work, not least that she didn’t find out about it until 2013, one year after she first drew the Doughnut Economics diagram. Have you ever “discovered” something that was already there, and did it transform your thinking as Kate Raworth said her discovery did for her?

Can we change our mindset “in a millisecond as the scales fall from our eyes”?

And if it happened would it be contagious as Tom Oliver suggests?

On radio the pictures are better (because they are in your brain) and listening to the clips of Dana Meadows lecturing I see rooms full of men – “crusty old scientists” as they are described at one point. How must it have felt to talk about dreams, hopes and vision in front of those audiences? How does it feel now, in the present day?

The possibilities are endless, do listen to the programme and join us on January 15th 2024.